The war, as the Surrealists predicted, has robbed us of our hidden terror, as terror can only exist if the forces of tragedy are unknown. We now know the terror to expect. Hiroshima showed it to us. We are no longer in the face of a mystery. After all, wasn’t it an American boy who did it?”

Barnett Newman

After the horrors of World War II came to a close with the dropping of, not “only” one, but two, atomic bombs, killing hundreds of thousands, the idea of ‘art for art’s sake’, seemed somewhat perverse. The philosopher Theodor W. Adorno stated that “to write poetry after Auschwitz would be barbaric”. This sense of alienation and the loss of faith in the old values echoed the rebellion of the dadaists movement, that sprung from the craters of World War I. It is often said that those who do not know history are doomed to repeat it. So it only seems fitting to turn our eyes onto the old works of art. Perhaps there could be something there that would help explain, or at the very least critique, this polarized cluster-fuck of a society we now find ourselves in.

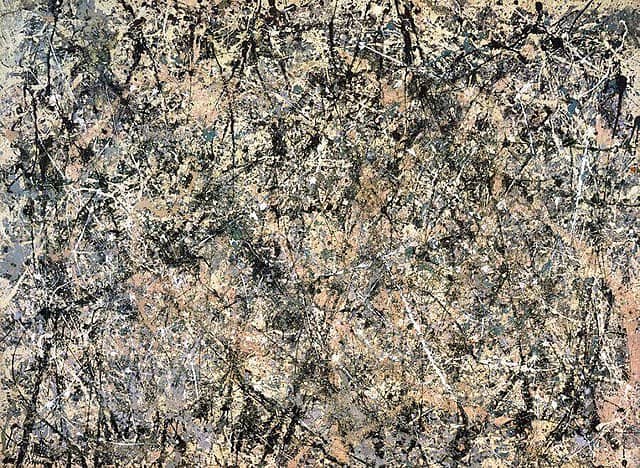

One of the artists attached to the movement of abstract expressionism, also called The New York School, was Jackson Pollock (1912-1956). Pollock would become famous for his action paintings where he would lay the canvas flat on the floor, drip, pour and splash paint onto it, using sticks rather than brushes. This way of painting allowed Pollock to access the painting from all sides. “When I am in my painting, I’m not aware of what I’m doing. It is only after a sort of ‘get acquainted’ period that I see what I have been about. I have no fears about making changes, destroying the image, etc., because the painting has a life of its own”, he said in an interview.

Pollock was famous for not wanting to hand the viewer a particular interpretation of his work. Later he would go further with this and abandon the more conventional titles, like; Autumn Rhythm, Mural on Indian Red Ground, and The Deep, to simply assign them numbers, so as not to guide the viewer into a given, preconceived meaning of his art. This approach certainly leaves his art open to interpretation. At first glance, Pollock’s drip paintings seem to be devoid of all political ethos but when viewed through the lens of Deleuze philosophy, some interesting things come to light.

Gilles Deleuze (1925-1995) was a French philosopher who is often grouped together with the post-structuralist and postmodern schools of philosophy. He published his first philosophical monograph, Empiricism, and Subjectivity, on David Hume, in 1953. Later he would go on to collaborate with the French psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Félix Guattari. Together they would write several books, the most important being the two volumes of Capitalism and Schizophrenia: Anti-Oedipus (1972) and A Thousand Plateaus (1982). I find it very unlikely that Pollock was aware of the philosophy of Deleuze, given that he died just three years after Deleuze came onto the philosophical scene, and also, it would take some time before Deleuze philosophy was fully realized. I am, however, confident that Deleuze was aware of Pollock’s work, however, I don’t know if it had any influence on his philosophy as such. As far as I know, Deleuze never wrote about Pollock or his art. With that said, Pollock’s art seems perfect for a Deleuzian interpretation.

The first thing that comes to mind when viewing a Pollock painting through a Deleuzian lens is the concept of ‘rhizome’. The paintings do not appear to have a clear beginning or end. There is no up or down, left or right. You could, for all intents and purposes, flip it over, turn it upside-down, and it would pretty much remain the same. It is a series of connections between lines of paint, a matrix where no intersection is more important than another. No objects or subjects appear in the paintings, only connections, and thus the most fundamental binary set, that of object and subject, has been broken down. This has profound implications for politics today, especially for what is often referred to as ‘identity politics’. I would argue that all politics is basically identity politics in one form or another. But almost all suffer from the same fundamental problem, which is that of identity. The idea that there is some essential thing, either inherent or given, in an entity that gives it its identity is fundamentally flawed. No inherent essences that give an entity its identity have ever been found, because once you think you have there are always some entities that do not fit the mold, so to speak. This is why a definition of Art has never, successfully, been made. There will always be works of art that diverge from that given definition. And if the essence is given then it is arbitrary and not essential, and thus cannot be used to justify why one is and the other is not, for example, why one person has rights and the other does not.

The world is more like a Pollock painting than Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People or John Gast’s American Progress. Society is not binary and easily categorized. It is more a series of connections that cannot be reduced to a single point and used as a stepping stone for who’s in and who’s out, who’s the subject, and who’s the object. So, identity politics can be criticized for being a lose-lose game where ‘molar segmentation’ plays a key role. The concept is used by Deleuze and Guattari to describe the binary machinery that labels people into one of two categories, the most fundamental of which are the subject/object distinction, but a more relatable one would be us and them. The process of identifying and categorizing into a binary set, i.e. molar segmentation, enables certain sanctions or consequences to be put in place. And it is not only descriptive but also normative. Because what inevitably happens is that you find yourself in a hierarchical system where one is deemed better than the other.

The strength of identity politics is to highlight the oppression certain groups of people are subjected to, an oppression that often has its roots in a more hegemonic form of identity politics. We don’t solve the problems we are facing by replacing one form of identity politics with a new, equally rigid form of identity. That would be like trying to transform a system of monarchy by replacing a King with a Queen.